COVID-19 in the wastewater: UW researchers track silent spreader in sewage

SEATTLE - As COVID-19 runs rampant in the Puget Sound, University of Washington scientists are tracking the virus in the one place most of us want nothing to do with — the sewer.

Handling raw sewage is something PhD student Sarah Philo and post-graduate Angelo Ong do on a weekly basis, donning layers of gloves and other biosafety gear, including respirators. It’s not for the wastewater, it’s for the virus living in it.

"Once we saw the pandemic starting to take hold, one of our first thoughts, in my mind, was that we should start measuring the virus in wastewater," said Scott Meschke, UW professor of environmental and occupational health services.

Meschke had initially refined the wastewater testing method working with the poliovirus. With a new outbreak in the Puget Sound, he was not surprised to find SARS-CoV-2 in sewage, the virus known in humans as COVID-19.

RELATED: King County to spend $7 million on COVID-19 vaccination sites, mobile vans

"Sewage is kind of the great composite sample, right, pretty much everything that passes through the body is going to exit one way or the other," he said.

He said it could hold one answer to tracking a silent spreader. That’s what he’s trying to refine in his lab, with Philo and Ong’s help.

Using weekly samples from three wastewater treatment plants in King County, the method to identify SARS-CoV-2 is "really low tech," according to Philo.

"It’s also really easy so we hope that there aren’t a lot of barriers for people to be able to do this method," she added.

Using raw wastewater, Philo and Ong test the pH and make sure there’s no chlorine in the sample, which could ruin the experiment. Then, it’s a combination of acid and skim milk to get the right balance. Philo said skimmed milk flocculation draws all of the viruses and bacteria present in the sample.

RELATED: All regions to remain in Phase 1 of new Healthy Washington reopening plan, state says

Part of the process includes the three samples going on a shaker machine for two hours. In total, the weekly testing is a full day of work for the UW students.

There’s talk, Meschke said, of wastewater being an early warning system of virus spread. Tracking the virus in King County samples since March, they’ve found their own results mirror clinical cases.

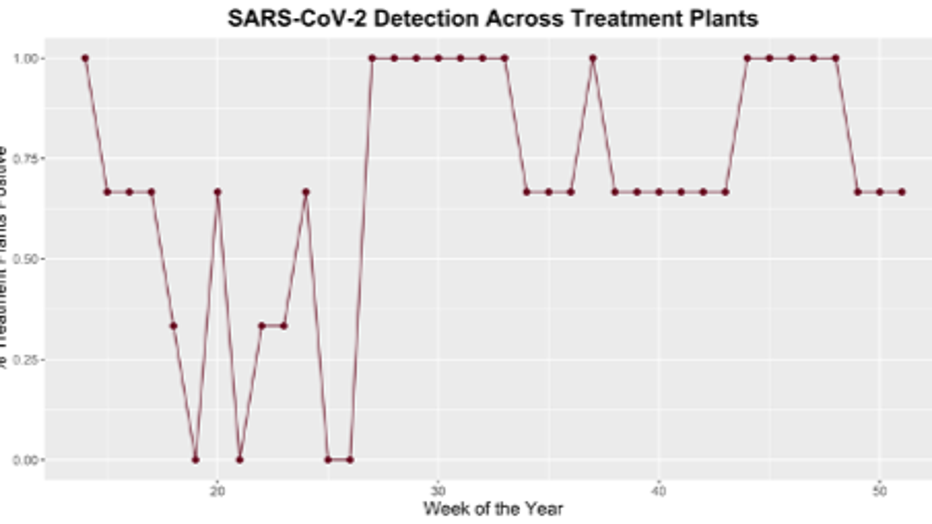

"Definitely over the summer, when there were fewer COVID cases in the Seattle area, we were not getting as many detections in the sewage so it was definitely lower levels, below what we were able to find," Philo said. "And as the number of COVID cases has risen we’re definitely getting much more detection across all three treatment sites."

A point with the value of one indicates SARS-CoV-2 was detected at all three treatment plants. A point with the value of zero indicates we did not detect SARS-CoV-2 in any of the treatment plants.

Right now, the results tell us what we already know — there’s COVID-19 in King County, found in testing and down the drain. But there’s more to tracking the virus than what has been recorded this past year.

"The prevalence is so high right now that we should expect to find it, but once we start knocking it down, this tool will be even more important to understand low levels of circulation in populations," Meschke said.

It’s an indicator that comes straight from the pipes, not impacted by human behavior.

"The benefit of that is we pick up asymptomatic cases or we pick up people that aren’t seeking testing," he said.

He acknowledges the method, right now, is less useful sampling massive water treatment plants, which only tell them that there’s COVID-19 in the county. The purpose of the research, he said, is to perfect a method that can be easily duplicated across labs around the country and world. The greatest use of tracking outbreaks, he said, will eventually be much closer to home.

"Nursing homes, dormitories, places like this where if we get a signal very close to the source, we’re able to immediately respond with additional follow up clinical testing," he said.

RELATED: Who's getting the COVID-19 vaccine next: A look at Washington's distribution plan

Opening an ultra cold freezer in the lab, Meschke takes us back to a time before doctors tested for COVID-19 in the U.S. Examining old frozen wastewater samples from February, Meschke said they were able to identify the virus in King County sewage, before testing and illness indicated the virus was spreading in the community.

As more of the population becomes vaccinated and people are eager to flush COVID-19 out of their minds, Meschke predicts testing will be less prevalent, allowing COVID-19 to silently circulate. The key to catching it in time may start with circling the drain.