Noise pollution harms endangered orcas, scientists are rushing to find solutions

SEATTLE - The southern resident orcas are in a rough spot: there is too little food for them to eat, their favored hunting grounds are contaminated and noise pollution makes it harder to hunt prey.

While a lot of work is underway to restore salmon populations to the Pacific Northwest, the work takes time. When you turn off an engine, or re-route large shipping vessels, the impacts are immediate.

Dropping that noise makes it easier for orcas to hunt what is still left.

Dr. Jason Wood, Sea Mammal Research Unit (SMRU) Consulting's managing director, told FOX 13 that their work aims at tracking, and coming up with strategies to drop noise volumes in the Northern Pacific Ocean is up against the clock.

"This is our little effort to stretch the clock out a little bit so they have a chance to recover," said Wood.

Wood was among the researchers that invited FOX 13 out onto the Sound Guardian – King County’s research vessel – to retrieve a hydrophone system that was placed in water near Shoreline back in February. That equipment has been beaming audio back to researchers – eliminating a "blind-spot" for researchers tracking noise pollution in Puget Sound.

Removing the equipment allows researchers to recover raw data that can provide additional information on what the soundscape is in a particular location. The ultimate goal is to get that data into the hands of people that are working to reduce, re-route or slow vessel traffic that creates noise pollution in our region.

"Once we better understand we can help inform mitigation strategies," said Wood.

Wood hopes that "Quiet Sound" – a local collaborative program to reduce noise pollution impacts on the southern residents from large commercial vessels – can utilize the information they are discovering.

Quiet Sound is similar to the ECHO (Enhancing Cetacean Habitat and Observation) program run at the Port of Vancouver. Like Quiet Sound, ECHO is a voluntary program focusing on critical habitats for southern resident killer whales.

A key to the ECHO program has been a voluntary ship slowdown in both Haro Strait and Boundary Pass.

According to the Port of Vancouver, underwater sound intensity has been reduced up to 55% in key southern resident orca foraging areas.

While plans to slow, or even re-route traffic, when orcas are nearby can have massive effects, some groups have a concern about the growing number of ships traveling the Salish Sea.

Nearly 9 million people live in the Salish Sea ecosystem – that includes people in both Washington state, and in Canada. By 2040, that number is expected to jump to 10.5 million people according to the EPA.

As more people arrive in the region, more cargo is expected to arrive by large shipping vessels. On top of that, you have refineries and other large-scale businesses that are planning expansions.

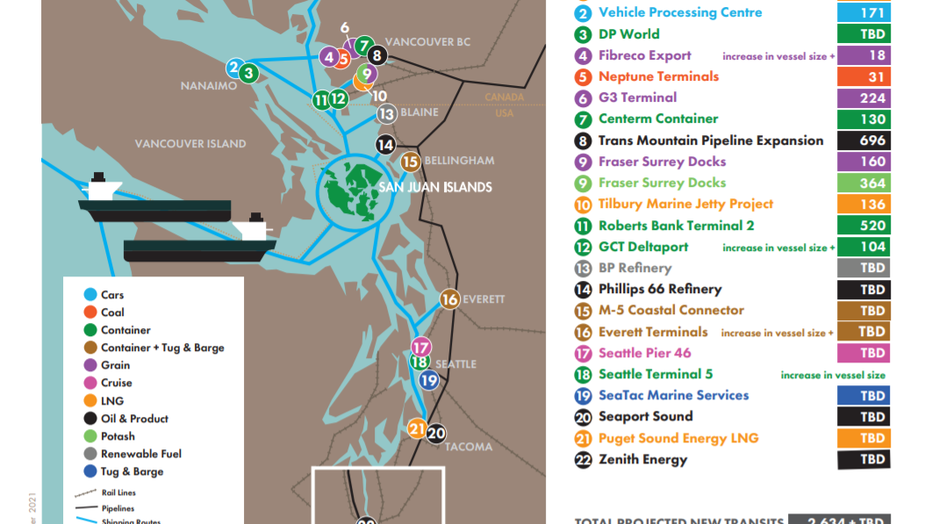

Friends of the San Juans, a non-profit environmental group, has been raising concerns about a looming shipping traffic boom. Their latest "vessel traffic projections" is tracking more than 20 projects that could expand the number of large ocean-bound ships traveling within the Salish Sea.

"For me, addressing vessel traffic is one of the areas where we can have the biggest impact," explained R. Brent Lyles, the group’s executive director. "It’s a big deal – there’s so many different pieces of the vessel traffic picture that can impact the southern residents’ survival. As a community, we need to take this seriously and do what we can to make sure that vessel traffic, as it increases, is not hindering the survival of our southern resident orcas."

There has been some focus on the issue of vessels, specifically the amount of traffic entering our local waters. When the Southern Resident Orca Task Force filed their final report in 2019, it had dozens of recommendations. Among them, a recommendation reading: "Determine how permit applications in Washington state that could increase traffic and vessel impacts could be required to explicitly address potential impacts to orcas."

According to the team at Friends of the San Juans, more work needs to be done.

According to Friends of the San Juans "Salish Sea Vessel Traffic Projection.," almost every Canadian project had revealed vessel traffic changes during their permitting process. The same was not true of Washington projects.

Friends of the San Juans latest vessel traffic projection identified 22 new or expanding terminal and refinery projects that have been proposed or permitted or were recently completed. (Friends of the San Juans)

In the latest update from the Washington State Recreation and Conservation Office, the specific recommendation linked to vessel traffic noted that progress has taken place, but work is needed. They listed two potential steps, while stating staff is needed to update checklists for the State Environmental Protection Act if they were to include vessel traffic numbers.

"That is a key recommendation that came out of that task force, and we need to do a better job as a community of getting caught up on this," said Lyles.

Lyles isn’t just concerned about the noise. He’s concerned about a growing potential for oil spills as more vessel traffic is added to Salish Sea. There is also a concern about the potential of ship strikes. His team believes that we’re operating with a key data gap: how many vessels are simply too many for our local marine wildlife.

SMRU Consulting’s Wood noted that even the best strategies to lower vessel noise come with drawbacks: slowing a ship can reduce noise, while slowing a ship by too much can reduce a captain’s ability to steer in tight quarters.

"There is a trade-off," said Wood. "You slow a vessel down and they make less noise underwater, however, you slow them down too much and they lose their ability to steer. There’s a sweet-spot with tankers and other vessels. They need to maintain momentum to avoid collision."

It’s a reminder of the delicate work unfolding that was once an afterthought. From shipping traffic to the noise produced by large vessels in our shared waters, scientists are scrambling to find a combination that satisfies industry, without harming endangered species.

It may sound like trying to thread a needle with solutions, but Wood believes there is a reason for hope.

"It’s dire," he said. "I’m concerned, specifically about this population, but as a biologist, I have to feel like there is a way to move forward. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be doing this."