Volunteers prove critical in the fight against invasive green crabs

KINGSTON, Wash. - To understand how serious Washington’s invasion of European green crab is, look no further than the amount of money the legislature earmarked for 2022: $8.6 million.

The money followed Gov. Jay Inslee’s mid-January emergency proclamation, but researchers say the frontline relies on more than money – it relies on volunteers.

This year, the Crab Team at Washington Sea Grant is monitoring 68 sites for the invasive species. Most of those sites are inland estuaries, and the sites are scattered throughout the state.

Since the beginning of the year, more than 100,000 European green crabs have been captured and removed from local waters. Those numbers are the work of plenty of hands.

"It’s a lot of shoreline to cover," explained Emily Grason, a marine ecologist running the Washington Sea Grant crab team. "So, if we’re not inviting everyone to participate we’re missing out on the chance to stop this in a meaningful way."

In the past few weeks, volunteers at Chuckanut Bay captured their first green crab during monitoring. Over in Kitsap County, a molt – an exoskeleton shed by a crustacean -- was found during a survey for another project.

"They’re very destructive to the habitat," explained Dr. Melissa Fleming, a program director for Stillwaters Environmental Center in Kingston.

Fleming oversees volunteers near Carpenter Creek, an area that has been monitored for years. They haven’t found the invasive European green crab yet, but surveillance remains routine. It helps with both early detection, and it gives scientists a better idea of change brought by green crab if, or when, they arrive.

"They impact the habitat so greatly because they’re not supposed to be here," said Fleming. They essentially have a party once they get here."

Unlike most native crabs that number in the hundreds during trapping at Carpenter Creek, the European green crab reproduces faster – they are capable of breaking down the habitat, and causing harm to shellfish, native crabs and the habitat that supports the early stages of salmon.

It’s the reason why European green crabs have drawn so much attention. They’re harmful to the ecology of the places they’re popping up, and the marine economy many people rely on – at a time Washington is paying attention to a number of endangered salmon species, the Southern Resident orcas, and a disappearance of kelp forests a green crab invasion can only serve as an unneeded stressor.

It’s why scientists are looking to sample routinely, even at sites that haven’t turned up green crabs for months – or years – on end.

"We may never be able to fully eradicate green crabs," said Grason. "By slowing the invasion we can buy ourselves time to figure out what and how to protect resources."

While volunteers are key, Grason also stresses that people shouldn’t simply comb beaches and eradicate European Green Crabs on their own. She said that most images submitted to them by the public aren’t the species they’re trying to remove from our area waters – so there is also a concern that people will unintentionally kill native crabs that are helpful to the local environment.

The best way to help Washington Sea Grant, WDFW and tribal governments that are on the front lines is to take a picture, record information on where you’ve made your discovery and release the crab back into the wild.

"We really need to avoid killing a lot of these crabs accidentally, because in some ways they’re our best fight against European Green Crab before they become established."

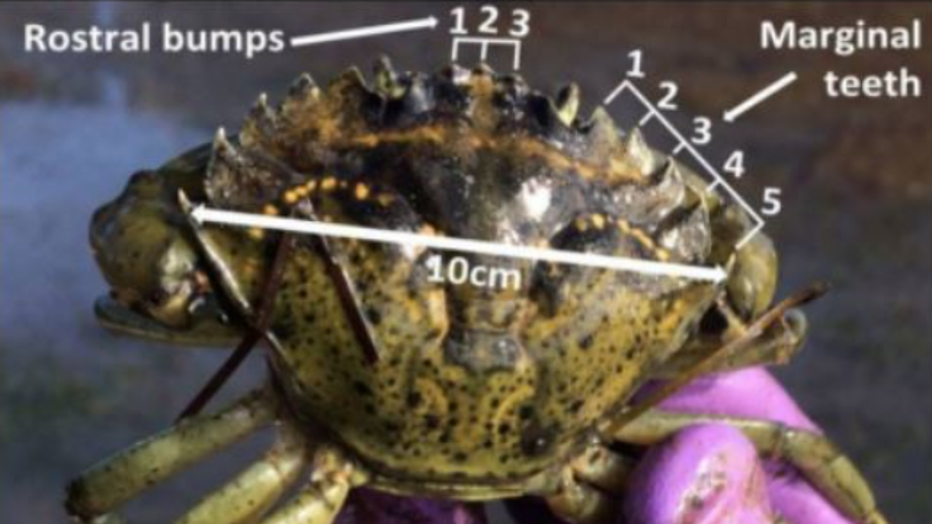

European green crabs are identifiable by their distinctive five spines, or teeth, on each side of their shell. While they’re called "green crab," their color can vary from reddish to green – they’re typically no longer than 3.5 to 4 inches across.

The easiest way to report a European Green Crab sighting is through WDFW, here.

If you are active outdoors, and keep tabs on a variety of invasive species, you can also use the WDFW Invasive Species Council app – downloadable, here for both iPhone and Google Play.